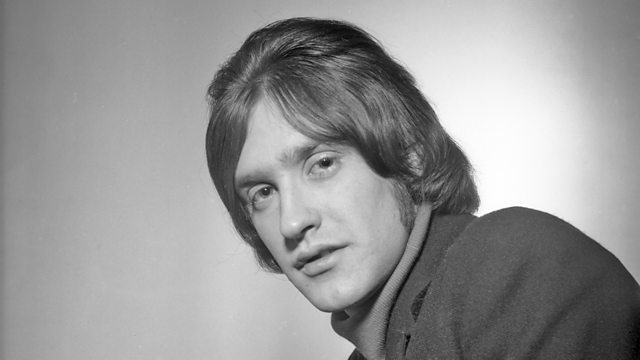

Founder of The Kinks, brother of Ray Davies and now back playing live in the UK for the first time in 13 years at London’s Barbican. Mark Raison (aka Monkey Picks) meets Dave Davies.

The first thing Dave Davies says when we meet around the corner from the Muswell Hill street he grew up in is ‘I like your jacket’. I tell him it could be one of his old cast-offs. ‘Maybe it is,’ he adds, proudly showing off his new Ben Sherman suit before talk turns to different types of a rounded shirt collar. As an introduction one of the most naturally stylish musicians of the 60s, it’s near perfect.

Now, fifty years from the first Kinks records and the unleashing of his incredible guitar sound that took ‘You Really Got Me’ to number one, thirteen years since his last London show, and ten since suffering a major stroke, Dave is back to play the Barbican in London this Friday.

Fifty years in the music business, are you looking forward to celebrating it on Friday?

Oh yeah. We’ve done shows in the States and the audiences have been great so when an opening came up at the Barbican and I thought it would be the perfect gig. Well, it could be, might be the worse one. People become really obsessive about these anniversaries. I said to Ray we should do something for our 51st anniversary. We’re talking about doing some things, we not sure yet. He’s always busy, I’m always busy. We get together for a pint now and again and talk about football. I think we’re getting closer to it but we’re getting older.

On your recent album, I Will Be Me, there’s a song ‘Little Green Amp’ that describes you as a kid at home, practicing your guitar, slashing your amp to create the sound you’d soon be identified with, the neighbours banging on the wall and you full of rage. What was the root of that rage?

I think primarily it was my childhood sweetheart, Sue. I fell in love at 14. These days it’s quite normal but in those days it was frowned upon. Sue got pregnant and they put her in what they called an Unmarried Mother’s Home to have the baby. It was devastating. My mum and her mum conspired to keep us apart. I didn’t find out until 1992.

Why did they do that?

[Twists finger to his temple] Her mum was already crabby and her daughter was an only child. The thought of her being pregnant and having a child out of wedlock and all that bollocks was too much. My mum, I think she saw music as a way out for me, being a boisterous sort of kid. I hated school. I hated that talking-down mentality, that condescending attitude. She thought she was being smart, but smart for whom? On ‘Little Green Amp’ I tried to reflect on how I felt at the time. The rage I had, the anger, but tried to keep it funny. The ultimate knife, dig, is the fact that me and Sue went to Selfridges and I bought her an engagement ring for a fiver. The look of horror and disappointment on my mum’s face. It took me quite a few years to come to terms with it. Who has the right to tell you what age you can fall in love? It’s not a science. I think that made me a bit disrespectful to women later on going out on the road with different girls and that.

The power of those early riffs is was quite extraordinary. What would’ve happened if you hadn’t come up with that noise for ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘All Day And All Of The Night’ that no one had really done before? After your first two singles weren’t hits, suddenly you were huge stars sitting at number one.

I think great things happen by accident. You can over-think things. I was talking to someone the other day about the guitar riff and people forget it wasn’t just about the guitar sound or the records, it was about the music, the fashion, the attitude, it’s all a package. That whole period was very unusual. That thing about working-class people doing something, expressing themselves. Whereas before it was rare for working-class people to get the limelight or to get important jobs.

Do you think that being working class influenced your music?

Of course, it did. When I listened to a lot of the early blues players you could sense the oppression in what they were doing. Although it was a totally different culture you could relate to the emotions. My uncle worked at King’s Cross on the railways, we didn’t get much money, and all these feeling about having to try hard to keep a family together, these feelings and emotions were the same.

Once you’d made it, you lived the 60s pop star lifestyle to the hilt, didn’t you?

Just about. It was amazing. Fresh out of school, cocky as hell, eying up all the chicks, you know. It was wonderful. Parties, people I met in the art world, the intelligentsia of London, I loved it.

And music gave you that. Without music, you’d never have had access to that world.

I think my mum knew that. As a way of getting us out there, of doing something more relevant. I think music saved me from a lot of things. Crime maybe, who knows? That’s why it’s very important for young people to have an artistic interest. We use the mind differently; thoughtful and more considered.

One of the things that comes across with your work with The Kinks is it’s not one over-studied playing style, it’s inventive, from ‘All Day and All Of The Night’ to the ‘See My Friends’ to ‘Waterloo Sunset’ to ‘Victoria’, it’s always different styles.

It comes from a background where there was so much music. My six sisters loved music, my Dad played the banjo, my oldest sister Dolly would listen to Fats Domino, Doris Day. They were all songs. When we got working in the studio we started to realise the importance of structure and where the guitar went, it’s not just all the way through.

Songs need something to embellish it, not to get in its way. It was an interesting learning curve for the first couple of albums. Also, because Ray being the main songwriter, with things like ‘Dedicated Follower Of Fashion’, where he really began to develop as a writer – or as I like to say, as an ‘observationalist’ – we realised certain sounds fit with lyrics or a line or melody. It gives it a different aspect rather than just playing a few riffs and going to the pub, although we did that as well.

Ray would come with the main idea of the song. How did the rest of the band add their contributions?

In that early time, in something like ‘Sunny Afternoon’, Ray would have the seed idea – the riff – and I’d always loved songs and riffs that go down – those descending chords – and then up. That’s why ‘Dead End Street’ has always been one of my favourites. I suggested to Ray to have a counter-riff on ‘Sunny Afternoon’, making it stranger. I was always interested in the unusual. On ‘See My Friends’ I think it was before they even had sitar music in local Indian restaurants. That was really a great thing to realise about the recording studio was if you had a sound in your head you could try to recreate it by detuning and exploring tones.

You can change the whole mood of a song just by tuning it differently or even by using a cheap instrument. It might sound tinny but it might fit the style of the song. Whilst everyone else out there was buying up the whole London contingent of sitars, we were doing it on a cheap Framus guitar. I liked experimenting with music.

And you liked experimenting with fashion too.

It’s very important. Me and Pete Quaife would meet for lunch when he worked as a graphic artist for The Outfitter and I worked at Selmer for a bit and we’d meet up and go to Berwick Street and down Carnaby Street – although it wasn’t really Carnaby Street then, just a few men’s tailors, a few women’s shops – and we had a thing where we’d buy anything. A silly hat, something like that, and if the older generation didn’t like it, and turned their noses up, we thought that was good.

I love that orange, red and purple felt hat you had. Do you remember it?

It was a cloth floppy hat I could turn inside out and wear all day. Yeah, it folded up. I got it from a ladies hat shop at the back of Carnaby Street, Kingly Street. It was like a tea cosy I could put on my mum’s teapot. I was down Carnaby Street the other day having a look around. The Shakespeare’s Head is still there, that’s where I met my lifetime long friend, a guy called Mike Quinn.

He worked in one of the first John Stephen shops and we got pally. I’d go to his shop to see what he had and he’d go ‘Dave, I’ve got this jacket. Take it out’ and I’d sneak it out the shop. So I had an eye for fashion, as did Pete who was into the same stuff.

Did you feel any affinity to the Mod movement at the time?

I did but I didn’t embrace it as much as Pete Quaife did. He had his Vespa and his parka and was really into it, he was the original Modfather. I liked the more elegant type things. I had a girlfriend who had centre-parted hair with the bouffant at the back and I’d copy that. Men’s fashions were so boring. Pete was the purest Mod in the band but I liked elements of both Mods and Rockers.

I liked the pill-taking of the Mods. I think The Kinks were maybe the first Mod band but The Who were the first Mod band that looked like it. The Small Faces were a real Mod band and The Action were absolutely great. Pete was into the Motown influences and making us do wretched versions of ‘Dancing In The Street’. We did a tour with the Earl Van Dyke band, and Earl taught Pete the bass parts he used to play on the keyboard in some of his songs. That’s where the idea for ‘Everybody’s Gonna Be Happy’ came from. If you listen to the bass parts, those chromatic things, they came from Earl Van Dyke.

After the first few Kinks hits The Who came out with ‘I Can’t Explain’ which was very much in your style. What did you think when you first heard it?

As The High Numbers, they opened for us a few times in Shepherd’s Bush and in South London so they’d had the chance to really suss us out. I remember the first time I saw them I thought ‘cheeky little buggers!’ They were an extraordinary band. When everyone was copying the Kinks for ideas it was only really Pete Townshend that owned up to the fact we were an influence.

It seemed to me when people don’t know what to do they dig out an old Kinks song, we do it. And David Bowie, he’s not exactly a closet Kinks fan but we were mates when he was Davy Jones in The Manish Boys, so he’s a secret fan. The Manish Boys were obviously lesser-known so when I couldn’t really go out of hotels because of the screaming girls I’d get David to bring a couple of girls up for me.

I hadn’t realised ‘David Watts’ was a real person. Can you tell us about him?

We did a gig, ’64-’65, in Rutland run by this David Watts, a retired Major in the Army. He was all dressed in his tweeds. ‘Jolly good show boys, why don’t you come back to the house afterwards and we’ll have a little drink’. So we go back but the dead giveaway was when he sat down and he was wearing pink socks. You have to realise homosexuality was still illegal right up until 1966. I was amazed when we first got into show business how many gay people there were. But they were always the funniest and the most creative. Anyway, this party progressed, we were getting a bit pissed, and David owned this land, lovely Georgian Manor, and Ray was going to sell me, to pimp me off, to this David Watts in exchange for this house. Cheeky c***.

Were you tempted?

No, I tried. I did try [with men] but I loved women too much. David took me upstairs and he had this training bicycle. ‘Why don’t you try it?’ So I’m cycling away and he’s being all flirtatious. We had a great time making ‘David Watts’. I often wonder about when The Jam did it.

Paul Weller being quite a serious guy I wonder if he knew the full backstory to that song. I used to take my son Martin to see The Jam at the Marquee and the Rainbow. When I was making my album ALF1-3603 in 1979 there was a knock on the studio door and Paul Weller walked in, very quiet, and under his jacket, he had a 45 of ‘Susannah’s Still Alive’ which he shyly asked me to sign it for him. Really sweet.

Do you think all the reports of fighting within The Kinks – not just you and Ray but you and Mick Avory – has been over-played?

It’s definitely been over-played. Of course, there was fighting, and we had difficult times when me and Mick were bumping heads, but we’d get sick of working that close all the time, in each other’s pockets. In the end, you have to say ‘Why don’t you just f*** off? Get out my face.’ But Mick became like an older brother and Pete. But Pete was a fun guy and just couldn’t stand it when the business when all dour, so he thought f*** this and left.

We were really good friends and he was a really good musician. Apart from mine and Ray’s many differences with music and ideas, the sense of humour we had, you learn as only siblings do. I think the humour really showed through a lot of The Kinks music. Even ‘Waterloo Sunset’ is quite amusing. The guy in the song could be a dirty old man in a mac. ‘I don’t need no friends.’ Not to put it down, as it’s an epic piece of observational writing, but we always had that other side to The Kinks. All that camp thing. Me and Pete loved it, camping it up, pouting. Even Mick Avory who was very macho in his expression would try it, even though it didn’t really come off on him. There was always humour.

Ray was under a lot of pressure to come up with the songs. Did you think if he didn’t come up with a hit record all this would disappear?

No, I didn’t. I don’t know why but I had this automatic optimism. I think that was because I was working with family. Our immediate family were big supporters of what we were doing. When you dry up, or think you have, all it might take is a visit to the pub and play shove h’penny with your Dad or your mates and it would give you ideas. When you think back to Kinks music, so much of it was drawn from family, friends, surroundings, who we were, holidays as kids, everything.

Do you think The Kinks were quite nostalgic looking?

No, I think we were quite forward-thinking. There’s this character on I Will Be Me – partly me, partly someone else – on a song called ‘Living In The Past’ about this longing for nostalgia. We all do it as somehow we think the past is better than the present. Is that to do with loneliness? I think for a lot of people always looking back at the past is a sign of being fearful for the future. We need to embrace the future a lot more, especially older people. There’s a line in the song that I really like ‘No matter what they do or say, the future’s here to stay’. So that was my advice to the guy in the song.

Mark Raison

Dave Davies plays his first UK concert in 13 years at The Barbican this Friday (April 11th), for tickets and info visit www.davedavies.com.