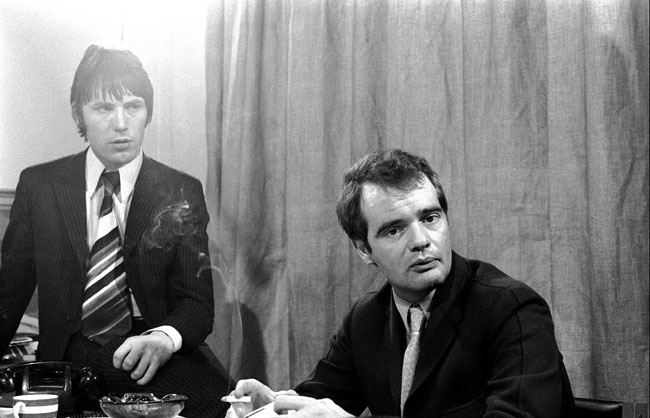

Alex ‘The Scenester’ Baxter checks out the Lambert and Stamp documentary. Yes, the men behind The Who’s initial success.

The meteoric career of Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, filmmakers turned pop group managers, hustlers and outcasts is the subject of a film, tautly directed by James D. Cooper, and coming your way in May.

That two people of such completely different backgrounds and little in common but a shared given name should get together at all, let alone in the newly emergent pop business of the early 1960s, is a perfect example of this freewheeling period, when class barriers came down and the children of the aristocracy and the workers rubbed shoulders. Christopher ‘Kit’ Lambert, the son of composer Constant Lambert, and Chris Stamp, son of tugboat captain Thomas Stamp and brother of actor Terence Stamp, met, significantly, at Shepperton Film Studio, which their charges, The Who, would one day own and to which Stamp would return for an unhappy meeting with them, and their lawyers, years later.

Using much archive and contemporaneous footage, the film’s 117 minutes flash by in an amazing journey across two of the most explosive, fascinating and significant decades of popular history.

Lambert’s early career choices, from Army service, to assistant director on films such as The Guns of Navarone and From Russia With Love, to his trek to South America to discover the source of an obscure tributary to the Amazon River, are the stuff of Boy’s Own stories.

His subsequent meeting with Stamp, working on films like ‘The L Shaped Room’ and ‘Of Human Bondage’ would form a lasting, if unexpected friendship and would take them from scratching their living in the precarious film world, to managing the career of one of the UK’s most successful, inventive and ungovernable rock bands.

Their joint decision to document the UK’s live music scene in the form of a film would prove a crucial one and the original footage is, as ever, the best way to show it. The haphazard meeting with The High Numbers, and our duo’s realisation that their film business might be augmented with taking on the management of this group of upstarts is narrated by Stamp and the now familiar story of the band reassuming their previous name, The Who, is spun out for old time’s sake. Doing any job in the film industry to ensure their young charges got a weekly salary; this is where the story really gets going.

The Who’s rise from a rough ‘n’ ready R ‘n’ B band and denizens of some of London’s more malodorous basement clubs, to a tough, choppy bunch of miscreants peddling a dissenting line in dark psychedelia, on to a wildly successful rock juggernaut, as much at home in the opera house, film studio or stadium venue, is documented brilliantly from behind the scenes and with valuable input from the surviving members of the band and other interested parties.

Lambert and Stamp’s physical resemblance to the stage personas adopted by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore in their first flush of success may be a coincidence, but one which shouldn’t be ignored. The inevitable question of ‘who was the more talented?’ could crop up here, and its answer could prove as elusive as the one about the other famous mismatched duo.

Obsessively committing so many of their charges’ public appearances to film, from interviews on French radio to jaunts in their Magic Bus, are all revealing not only for period detail, but for what they tell you about the band and this singular duo. Lambert’s ease at speaking French and German in the course of these clips, added to his aristocratic manner, are pointers to how these chancers got away with their gloriously spendthrift behaviour, all affectionately recalled by Stamp.

Almost entirely buoyed up by credit obtained from bank managers impressed by Lambert’s top-drawer home address and demeanour, we are served up another strand of the broader picture of life in privilege-ridden 60’s Britain. Pete Townsend’s hilarious story about the wine shop where he has had an account for over forty years, and has never been asked to settle it, is a highlight, as is Pete’s rancour at the success of Track acts like Jimi Hendrix, Thunderclap Newman and Arthur Brown, all scoring number 1 hits, an honour which eluded The Who.

The revealing section dealing with ‘Tommy’ is perhaps the most interesting of all, with Pete recalling being accused of vanity by Lambert, in wanting to write an opera. Lambert and Stamp’s involvement in this most successful of projects is argued about, Pete maintaining his primacy in the writing, although giving honest praise to John Entwistle for his essential contributions. Footage of the work’s appearance at the New York Metropolitan Opera House shows middle-aged Americans coming out generally appreciative, a sign that even the more straight-laced were beginning to warm to the rhythms of rock and roll. It is also the section where the cracks in the manager/band relationship begin to show.

Lambert’s dislike of Pete’s ambitious, but thwarted project ,‘Lifehouse’, Lambert’s descent into drug addiction and Stamp’s into alcoholism spelt the beginning of the end of this relationship, brought out well, if painfully in narration, and ending in Lambert’s untimely death in 1980.

Stamp’s recalling of the fateful Shepperton meeting is poignantly, yet humorously brought out, as accused of mismanagement by the lawyers, he tells the band, ‘You now own this studio, do you call that mismanagement?’

The Who’s internal troubles are never very far away from our screen either; Pete’s anxiety over his own ability to deliver high standard material (no, really), his suspicions that Keith and John were, at one point, ready to jump ship and join Led Zeppelin (‘Some heavy metal band’, Pete’s classic put down, stings like acid) and the effect on Pete’s mind of the increasing workload during the recording of ‘Quadrophenia’ are all brought out well.

Those who can’t stay away from this film may well be coming to see the fascinating clips of their favourite band, rather than to hear the little told story about their managers, but the clips are astounding; exploding human jack-in-the-box-Keith Moon, looking about fourteen years old, playing the tiny drum set on ‘I Can’t Explain’, morphs into a gap-toothed, chubby clown, the moody, immobile John Entwistle, the cheerful but no-nonsense manner of Roger Daltrey and the troubled perfectionist Pete Townsend, are mesmerising.

Perhaps we should also give a thought to the two men, no longer with us, who helped the band on their road to international success, and whose meeting, unlikely then, seems a virtual impossibility to reproduce in today’s once more class-divided society.

Lambert and Stamp is available to buy now on DVD and Blu-ray. You can also rent or download it via Amazon Prime.