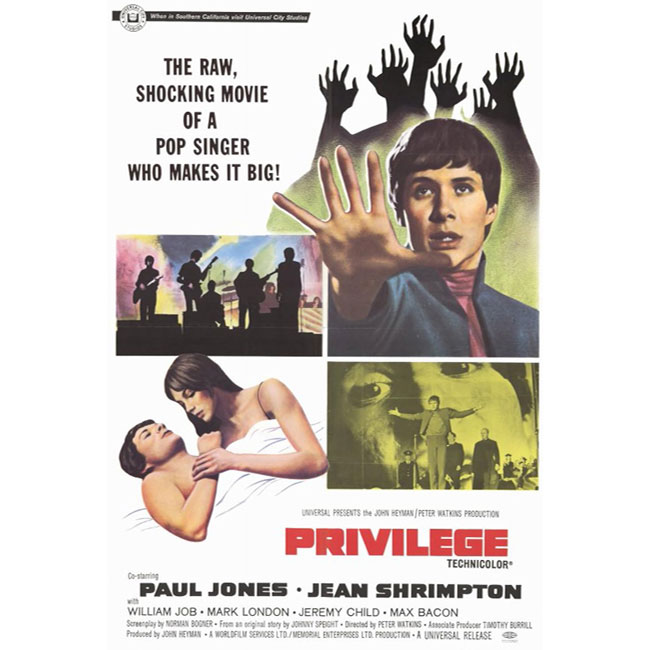

Something of a lost gem, Privilege (1967), is worth checking out if you like bizarre 1960s cinema with a message.

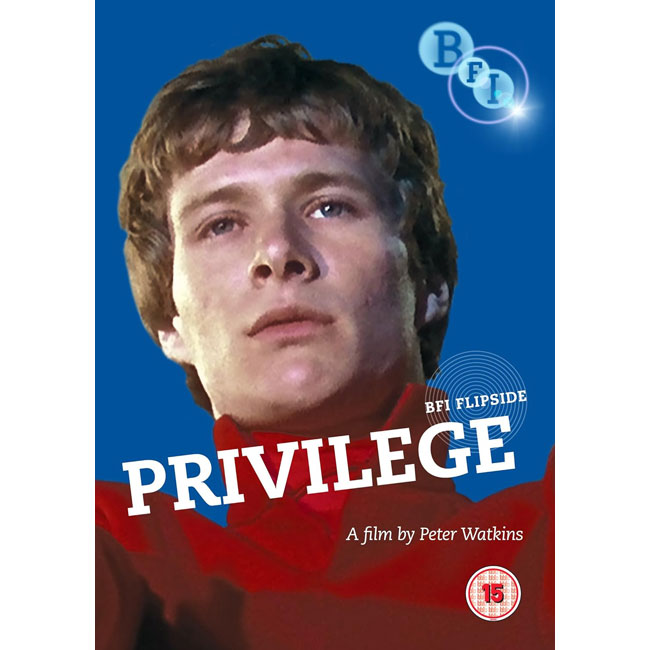

Some movies gain a reputation by being seen. Others, like Peter Watkins’ Privilege, are noted for exactly the opposite reason. Or at least that was the case until Flipside (via the BFI) gave it a release. But it’s still not something that gets a lot of screenings.

To be fair, it got a right old kicking from the critics in ’67, but time has been kind to Privilege since. As has the world we live in, which actually makes this bonkers idea far more believable.

Set at a time of a coalition government (Labour and Conservative policies are so similar, they simply run the country together), we discover that the biggest name in the country is pop star Steven Shorter (played by real pop star Paul Jones). His stage act, which sees him imprisoned and abused onstage, is designed to create anger amongst his audience – taking away their anger from the wider world around them and, indeed, the government.

On the back of this public adoration, Shorter is also a commercial and political tool. Run by committee (with government backing), his music is played on every station; he fronts a chain of Steven Shorter discos UK-wide and dominates consumption of everything from dog food to fridge freezers. If the country’s leaders want to sell something, they stick Steven’s face on it. When the UK has an apple glut, Shorter is brought in to ‘front’ an ad campaign encouraging us all to eat 6-a-day of the things.

But the ruling elite wants even more of Shorter – they want him to bring the public back to the church. Using an all-new stage act where the pop star ‘repents’ and finds faith at a rally at the national stadium, Shorter fronts the ‘Christian Crusade’ backed by funky versions of Onward Christian Soldiers and Jerusalem by a house band, some faith healing and fighting words by the church. It’s all reminiscent of totalitarian states – a world where everyone conforms to the ‘common good’ and intolerance is not accepted.

But that’s exactly what’s coming from Steven Shorter. In his spare time, he’s being painted by artist Vanessa Ritchie (Jean Shrimpton). But not only that – she’s asking questions of him and about him, questions that, over time, put doubts into Shorter’s head. And on live television, during an awards ceremony, it all comes crashing down as he shows his anger at being unable to live his own life.

As I said, Privilege was hammered by critics back in the day, partly due to its anti-establishment theme, partly because few thought the scenario was even vaguely believable and partly because of the ineffectiveness of the leads. That’s not necessarily the case.

The scenario is all too real in the 21st century, when ‘celebrity’ drives pretty much everything, from consumption to the news agenda. Entertainment in the modern era does have the ability to take our minds away from the real problems and concerns of the world. A coalition government through a lack of policy differences isn’t all that far-fetched either.

As for the leads, well, they work too. Up to a point. Jones perhaps lacks the charisma the pop star role needs (despite operating in that area as a day job), but he certainly has the fragility required for the latter stages of the movie. Shrimpton quite obviously isn’t a big screen natural – you struggle even to hear her at times. But she’s a scene stealer every time she appears. She wasn’t the face of the 1960s by chance you know.

But the biggest plus of Privilege is Peter Watkins. A controversial figure, he had come to the movie business after his most prominent work, The War Game, was banned by the BBC. He wasn’t willing to pull any punches for the big screen, either.

The film is part mock documentary and part movie. Slightly disconcerting at first but very effective in getting across the scenario, the world of Privilege and the succession of shady figures that run it. Everyone from Shorter’s minder and anarchist music arranger to the businessmen with the ‘real’ power sitting on the ‘committee’ has their own (less than likeable) personalities and quotable lines. There’s a real attention to detail here, which means Privilege is the kind of movie that can take repeated viewing.

Of course, there are holes in the movie – Shorter’s ‘act’ for a start, Vanessa’s ability to ‘break’ Shorter in such a brief time and to some extent, the idea that the entire population will buy into one pop star. But let’s be honest, since when did a film have to conform to logic completely?

Overall, Privilege is a decent watch and one that’s ripe for reappraisal. Unlikely ever to shake off the words ‘cult classic’, it’s a movie that has blossomed with age despite being still very much of its age. If you love leftfield movies of that particular decade, you’ll love Privilege. And if you don’t…well, why are you reading this?

As I said, it did get a reissue via Flipside at one point, and copies are available. Although not as cheap as you would expect. If you get the Blu-ray, there are plenty of extras, such as a booklet about the film and some early work by the director. If you see it cheap enough, it might be worth picking up.